Silence, AIDS and Sexual Culture in Africa

|

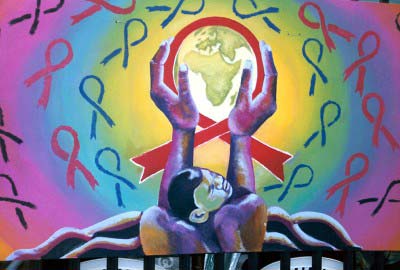

| © 2000 Ketan

K. Joshi, Courtesy of Photoshare.

A mural in Durban, South Africa promotes awareness

about HIV/AIDS in Africa at the 13th International

AIDS Conference. |

"There is a mystery at the

heart of the AIDS epidemic in Africa that scholars

have explored but have been unable to explain...The

mystery... has to do with that stubborn and multi-layered

AIDS silence, or what the professionals call 'the

denial' that has consistently characterised the AIDS

pandemic in Africa... The silence has to do with...

that much used and abused, dearly beloved sacred cow...

called 'culture'. In the two weeks following the AIDS

2000 Conference, incidences

have impressed upon me, once again, the hopeless situation

of women in the face of AIDS...

Thandi, shortly after her wedding,

inherited two orphaned children from her sister-in-law

who had died of AIDS. Now, a second sister-in-law

is dying of AIDS, and her sickly baby has constant

diarrhoea. What bothers Thandi is the fact that she

is a trained nurse, equipped with knowledge that might

be helpful: but as a sister-in-law, in her husband's

home, and one without a child of her own, she dare

not open her mouth. How could she suggest that there

might be something seriously wrong with the baby?

They would say that she is jealous... She keeps quiet.

Perhaps she herself will be the next sister-in-law

in that home to go down in silence...

People in KwaZulu-Natal are dying

like flies. Going to funerals has now become the premier

weekend activity, as it was in the late 80s to early

90s, during the 'total onslaught' years. Admittedly,

this epidemic is not only affecting women, but their

stories have a special poignancy that is embedded

in a kind of silence and helplessness that does not

affect men. Millions of women are being squashed under

the weight of the compounded multiple silences of

AIDS. Has the AIDS 2000 'Break the Silence' Conference

really helped them?...

More than anywhere else in the world,

the advent of AIDS in Africa was met with apathy,

or what some researchers have called 'an under-reaction'.

This was noted at all levels of society, whether individual,

communal or national. This under-reaction stood in

stark contrast to responses in other parts of the

World. In Europe, the USA and Australia, for example,

marked sexual behavioural change indicated drastic

developments in the first year of HIV/AIDS being seriously

discussed. In Thailand, the first evidence of the

arrival of AIDS saw a rapid dwindling of clients at

brothels, to the extent that many were forced to close

due to lack of business. The scenario for both North

America and parts of South America was similar. It

was recognised that prevention education campaigns

would have to constitute a sustained effort. These

reactions occurred as a response to HIV levels that

were a fraction of those found in Africa. Yet, no

such reaction was recorded for Africa...

The general lack of behavioural

change was once attributed to scant information. Over

time, this explanation has become less tenable, as

ongoing studies demonstrate a combination of adequate

knowledge with continued high-risk behaviour. Today,

there is hardly any doubt that more intensive or better

constructed information campaigns will do little to

change behaviour...

By turning our collective attention

to academic debates on the origins or existence of

AIDS, we are conveniently avoiding facing up to sensitive

issues around sexual culture. By pinning our hopes

on vaccines and cures, we risk 'over-medicalising'

our engagement with AIDS. We simply cannot afford

to get lost among the trees and lose sight of the

forest, the latter being the socio-cultural-sexual

context that provides such a fertile breeding ground

for HIV/AIDS.

More provocative still is the evidence

that has been gathered since the AIDS epidemic began

in Africa on the sexual culture that characterises

much of sub-Saharan Africa, specifically with regard

to levels of premarital sexual relations and extramarital

relations. There is a significant body of well-researched

and well-documented social science studies that points

to high level of premarital sexual activity, extramarital

relations and sexual violence, making African societies,

taken as a whole, more at risk for both STDs and HIV/AIDS

than those in other parts of the world. In many communities,

women can expect a beating, not only if they suggest

condom usage, but also if they refuse sex, if they

curtail a relationship, are found to have another

partner or are suspected of having another partner.

'Gifts for sex' is a practice that

expresses itself most strongly in premarital and extramarital

relationships... Only recently, with Christianity,

has sexuality become bound up with religious belief

systems that imply sinfulness, and it has never been

related, as in Europe, with romanticism. Sex, then,

could be viewed rather more objectively and instrumentally

in an African context. Selling sex for money or other

material benefits in the face of Africa's entrenched

poverty and women's continued financial dependence

on men is one form of transactional sex."

"From my own research with

young people in townships around Durban, there is

quite clearly another prevalent form of transactional

sex....It involves girls eagerly and easily exchanging

sex to pay for chain-store accounts, cell-phone bills,

designer-label clothing, etc... As one young woman

commented: 'If I want jewelry and other nice things,

I must get them now. After we're married, forget it!

Our men are awful'...

Along with the general under-reaction

to the growing epidemic... there is, a great reluctance-

that some have called 'a refusal' - by Africans to

come to terms with the real sexual cultures of their

societies... There are widespread beliefs that males

are biologically programmed to need sexual relations

regularly with more than one woman, and often concurrently.

Such beliefs are logically consistent with societies

that were traditionally polygamous...

Studies consistently suggest that

sex is regarded by the young as necessary, natural

and an expression of love, as well as an activity

that their peers expect of them if they are to be

considered 'normal'. The use of a condom is taken

as a sign of mistrust, as well as the hallmark of

one who indulges in casual sex. Condom use in marriage

is almost unheard of. Partner dynamics are characterised

by an avoidance of direct communication, with the

assumption that men should control the sexual encounter.

Common to both young men and women

is the belief that a man has a right, or even duty,

to force himself onto a woman who displays reluctance

or shyness. Gender-based violence itself is often

seen as a sign of affection, showing how deeply the

man cares. Sex in marriage is simply expected as part

of the marriage 'deal' whenever the husband demands

it. Indeed, even in cases where the woman discloses

her HIV-positive status to a husband, studies show

that the husband is likely to continue conjugal relations

with her while refusing to be tested himself...

What emerges most clearly from all

these studies is the fact that there is an urgent

need to recognise and accept the nature and shape

of contemporary sexual practices by men that have

dire consequences in the wake of AIDS. By turning

our collective attention to academic debates on the

origins or existence of AIDS, we are conveniently

avoiding facing up to sensitive issues around sexual

culture. By pinning our hopes on vaccines and cures,

we risk 'over-medicalising' our engagement with AIDS.

We simply cannot afford to get lost among the trees

and lose sight of the forest, the latter being the

socio-cultural-sexual context that provides such a

fertile breeding ground for HIV/AIDS.

This points to the crux of the heavy

silences that nourish AIDS in Africa, including the

silences and denials of governments. What needs to

be addressed is the role of men, particularly their

attitudes and behaviours that reflect their sexual

irresponsibility and a certain death sentence, not

only for themselves, but also for millions of women

and children...

Firm measures on the part

of government to foster the transformation of the

sexual attitudes and practices of young and middle-aged

men will run the risk of inciting the hostility of,

politically, the most dangerous section of the population.

Perhaps this explains why the issue is so carefully

avoided. But until such measures are taken, and our

leaders speak out with vigour and determination we

will continue to re-enact the high-risk sexual culture

and the silence that enshrouds it..."

By Suzanne Leclerc-Madlala. Dr. Leclerc-Madlala is a medical anthropologist and lecturer in the School of Anthropology and Psychology, University of Natal. AIDS Bulletin. September 2000. Reprinted with permission.

|