Muslims' Perspectives on Key Reproductive and Sexual Health Issues

|

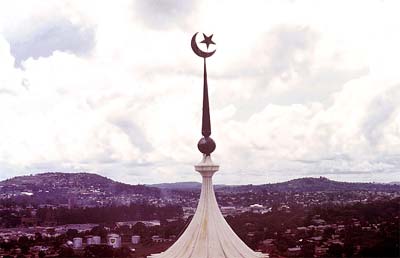

| © Board of

Regents of the University of Wisconsin System,

Courtesy of africa focus |

BACKGROUND

Reproductive health strategies are built around a

core belief that women as full, thinking, feeling

personalities, shaped by the particular social, economic,

and cultural conditions in which each of them lives,

are central to their own reproduction (Freedman and

Isaacs, 1993). Consequently, these authors argue,

health policies and programmes cannot treat reproduction

as mere mechanics, as isolated biological events of

conception and birth; rather they must treat it as

a lifelong process inextricably linked to the status

and roles of women in their homes and societies.

Evolution of the Concept

of Reproductive Health

The available literature reveals a high degree of

overlap between definitions of reproductive health,

sexual health and maternal health. The major international

encounters that have taken place since the Cairo conference

have shown that reproductive health has tremendous

potential to bridge gaps between diverse constituencies.

But the concept of reproductive health is also a cultural

product that emerged as a result of a particular historical,

legal and ethical evolution. Implementing it involves

not merely the application of principles and the selection

of measures, but a process of translation across cultures.

Therefore, a cultural perspective that clarifies the

link between the global and the local must be developed.

According to various definitions,

the basic elements of reproductive health are: responsible

reproductive/sexual behaviour, widely available family

planning services, effective maternal care and safe

motherhood, effective control of reproductive tract

infections (including sexually transmitted diseases

(STDs and HIV/AIDS), prevention and management of

infertility, prevention and treatment of malignancies

and elimination of unsafe abortion. These definitions

call for action to consider these demands as human

rights.

Examining the different definitions,

one observes that reproductive health is not defined

by strict criteria. The concept extends beyond reproductive

ages, reproductive events or reproductive organs,

toward a broader perspective on reproduction as situated

within a socioeconomic context. As a result, there

are no precise guidelines about the exact scope of

the concept, or explicit standards for inclusion or

exclusion.

Several major international conferences

in the population and health fields have taken up

the call for comprehensive reproductive health strategies,

and have begun to elaborate what this would entail.

Discussions of reproductive health strategies acknowledge

the close relationship between health and the social

and cultural contexts in which people live and exercise

their health behaviour.

The concepts of 'autonomy' and 'choice'

which are pivotal in international population debates,

are influenced by social and cultural factors that

vary widely, even within one region or country. Jacobson

(1994:26) defined autonomy as 'an individual's ability

to think and act independently of others to achieve

her\his interests'. However, the Western notion of

autonomy which is based on concepts of privacy and

individual rights may be less relevant to Muslim women

who value the interdependence of individuals, families,

and communities.

WOMEN'S STATUS AND AUTONOMY

WITHIN ISLAMIC CULTURAL CONTEXT

A husband and wife form the nucleus of a family. Their

relationship is described in the Quran as having two

major qualities: love (passion, friendship, companionship),

and mercy (understanding, reconciliation, tolerance,

forgiveness) within the overall objective of tranquility

(Omran, 1992). The Quran explains what this means:

"…and one of Allah's

signs is, that He has created for you mates from

yourselves, that you may dwell in tranquility with

them, and has ordained between you Love and Mercy" (Sura 30:21)

Many authors indicate that the status

of Muslim women evokes two contradictory sets of images

(Obermeyer, 1992). While the demographers, sociologists

and anthropologists indicate that the women in Muslim

countries have a lower status (Freedman and Isaacs,

1993; Weeks, 1988), the theologians argue that Islam

itself gives women a high status (Omran, 1992). Based

on the interpretation of the Quran, the theologians

argue that a woman is considered to be equal to a

man in many social and economic aspects (Omran, 1992).

For instance, she has the right to choose her husband;

in marriage, she has the right to keep her maiden

name; she can be completely independent financially

and has the right to do with her money as she pleases,

while the husband is responsible for providing for

her and her children (Omran, 1992).

The first image, which is painted

by the demographers, sociologists and anthropologists,

implies that the lower status of the Muslim women

is part of the explanation of high fertility in most

of the Muslim countries. The relation between lower

status and high fertility is believed to operate in

two mutually reinforcing ways (Obermyer, 1992): first

lower status means restricted access to education

and employment; and second, a woman's economic dependence

puts her in an insecure position, making the threat

of divorce and polygamy more menacing. These, thus,

limit her choices with regard to childbearing because

the one chance to improve her bargaining power and

to insure against risk of divorce is to produce sons

whom she can influence and rely on for support.

The second image of the Muslim woman

is that painted by the theologians. Omran (1992),

argues that the status of women in Islam is seriously

misunderstood for many reasons. It is wrongly implied,

he observes, when the behaviour of individual Muslims

and Muslim communities are interpreted as reflecting

the tenets of Islam. This is further compounded by

misconceptions about the status of women in Islam

based on the gross abuse of Islamic laws among some

ignorant Muslim groups. In addition, most of the Muslim

communities exist in the Third World which is associated

with the low status of women.

Obermyer (1994) argues that there

are aspects of Islamic doctrine that could be used

to reinforce the case for women's autonomy and equality,

which have received a great deal less attention than

the aspects of the doctrine which tend to promote

inequality. The author maintains that many Muslims

believe that statements in the scriptures that stress

equality of believers before God are the authentic

message of Islam, while those suggesting discrimination

against women are merely reflections of the temporal

conditions in which the religion developed, and a

distortion of its inherent egalitarianism.

CULTURAL CONTEXT OF REPRODUCTIVE

CHOICE

Many researchers have made efforts to link human rights

and reproductive health (Freedman and Isaacs, 1993;

Cook, 1993). The idea of reproductive choice has become

the focus of systematic elaborations based on legal

and ethical principles. One of the central elements

that define reproductive choice is autonomy, which

means that a woman can make decisions in matters of

reproduction and that she has access to the information

and services that can make her choice an reality.

Islamic laws are often seen as incompatible

with international human rights (Obermyer, 1994, 1992).

However, some Muslim authors retort that the standards

governing rights and choice as defined by the West

are contrary to Islam (Omran, 1992). They maintain

that certain infringements on women's freedoms are

mandated by Islam. However, applying the criteria

derived from international conferences to the analysis

of reproductive choice in Islam is difficult, because

of the existing differences in views on the relationship

between Islam and women's status (Obermyer, 1994).

Ahmed (1992) argues that there is

a basically egalitarian ethos in Islam that was distorted

by patriarchal forces. In his view, the religious

texts can and should be interpreted in a more egalitarian

manner. This perspective would be in harmony with

the Western notion of women's reproductive choice.

Obermyer (1994) supports this notion and argues, further,

that there are several aspects of Islamic doctrine

that are clearly compatible with such an interpretation.

She notes that a number of statements in the scriptures

stress the idea that God does not wish to burden the

followers, and suggest that quality is as important

as quantity in child bearing. In addition, a generally

positive attitude exists toward sex in marriage in

the Islamic context, as does a clear recognition of

woman's right to sexual enjoyment.

Obermyer (1994) examined two case

studies that represent interesting links between state

goals, gender issues, and reproduction. The first

is Tunisia, where the state carried out pervasive

reforms to improve both women's status and reproductive

choice without violation of the Islamic tradition.

The second case is that of Iran, where successive

regimes have implemented contrasting policies that

have had a direct impact on women and reproduction,

and where issues related to women have been affected

by political struggles at local, national, and international

levels. She concludes that the constraints on reproductive

choice are a function of state politics rather than

a reflection of religious doctrine, and that leaders

do, in fact, use Islam to justify divergent positions

on gender and reproduction. She states that:

"Like other religious doctrines,

Islam has been used to legitimise conflicting positions

on gender and reproductive choice. The ways in which

the ethical code of the religion is translated into

policies affecting women's status have been a function

of the ideology of groups in power and have been

influenced by changes in the economic, political,

and social spheres." (p:49)

The following sections examine the

concept of choice regarding certain aspects of reproductive

health, namely, abortion, sexuality and contraception

in the context of culture.

Abortion

The main concern for theologians is whether the Shari'ah

is supportive of abortion or not. From this general

question, a list of sub questions would arise:

In the interpretation of the Quran

and Hadith, direct reference is made to the “ensoulment”

of the foetus 120 days after fertilisation. At the

same time, some of the commentators of the Quranic

texts, hold that the words 'Khalqan akher' (i.e. another act of creation) in the Quranic verses

signify the "ensoulment" of the foetus;

and that the stage of 'mudghat ghayer' (i.e.

the lump not yet completely created) in the Quranic

verse refers to the stages when no soul had yet been

breathed into it (Madkour, 1974).

In summary, there are three main

stages in a pregnancy that influence Islamic scholars'

assessment of abortion:

i. Before 40 days

ii. Before 120 days, and

iii. After 120 days.

As was mentioned earlier, the fundamental

question for the Islamic law is at what point

during the process of development does a foetus become

a human being? According to Mussallam (1978),

Muslims believe that point is at the end of the fourth

month of pregnancy, when the foetus becomes “ensouled”.

There is another view, which locates that point at

the end of 42 days, when organ differentiation starts

(Omran, 1992; Mussallam, 1978; Madkour, 1974).

In summary, there is a consensus

among Islamic scholars that abortion after 120 days

is not allowed. However, Islam gives women a right

to abort in cases of severe maternal health problems.

However, these rights are relative and should still

be weighed against other alternatives.

Right to Contraception

The right to contraceptive use is discussed by many

scholars in detail (Omran, 1992). Most of the theologians

are of the opinion that non-permanent methods of contraception

are allowed in Islam provided that they are safe and

they are accepted by both husband and wife. However,

the question of permanent methods (male and female

sterilisation) still needs clarification. Most of

the theologians are of the opinion that these methods

are not allowed except in cases where the health of

the mother is in danger.

The objection to sterilisation arises

from the perception that the woman may possibly regret

this decision at a future date due to a renewed desire

to conceive (Rispler-Chaim, 1993), especially within

the context of the irreversibility of sterilisation.

Another argument is that it is an attempt to change

what God has created (Jad el Haq, et al 1992). In

addition, some scholars indicate that sterilisation

is by analogy like castration, which is prohibited

by the Prophet (Madkour, 1974).

Abdullah observes:

We used to participate in

the holy battles led by Allah's Apostle and we had

nothing [no wives] with us. So we said, "shall

we get ourselves castrated?" He forbade us

and then allowed us to marry women with a temporary

contract and recited to us [from the Quran]: 'O

you who believe! Make not unlawful the good things

which Allah has made lawful for you, but commit

no transgression.'

(Sura 5:87)

Rispler- Chaim (1993) and Omran

(1992) argue that sterilisation, if reversible, could

be viewed as one more variation of “legitimate

contraceptives”. Furthermore, sterilisation

is not similar to castration. While castration involves

impact on virility and fertility and the level of

the hormones, sterilisation affects fertility only.

It is argued that if the short-term methods are allowed,

then, the long-term methods should also be allowed

(Rispler-Chaim, 1993).

On the other hand, Serour, (1998)

suggests that the argument that sterilisation is reversible

is not true, the success rate of the procedure is

very low, it is expensive and needs advanced techniques.

RIGHTS TO SEXUAL HEALTH

AND SEX EDUCATION

This following section argues that Islam provides

both women and men the right to proper sex education,

good sexual health, and sexual enjoyment.

Reproductive Health and

Sex Education in Islam

At the time of the Prophet, sex education was given

side by side with other teachings of Islam. The followers

(men and women) used to ask about their sexual problems,

and the Prophet used to clarify what was obscure.

In addition, women used to ask 'Aisha', the Prophet's

wife, about some aspects of reproductive health. Sex

education is mentioned in the Quran and the Hadith

as follows:

-

Sexual Positions. Any position in sexual intercourse may be taken

namely, sitting, standing, and leaning on one side:

According to the Quran: “Your wives are

as a tilth* unto you so approach your tilth when

or how ye will." (Sura 2:223).

(* Tilth literally means a farm).

-

Family Planning. Abu Sa'd Al-Khudrei says:

We got female captives in the war booty and

we used to do coitus interruptus with them. So we

asked Allah's Apostle about it and he said, "Do

you really do that?" repeating the question

thrice, "There is no soul that is destined

to exist but will come into existence, till the

day of Resurrection." Al Boukhari.

-

Extreme forms of Sexual

Behaviour. Ibn Abbas narrates:

A man came to the Prophet and said: Verily I

have got a wife who does not retract the hand of

a toucher [nymphomania?]. The Prophet said: "Divorce

her". He said : "I love her". The

Prophet said: "Keep her in that case." (Al Boukhari).

It is worth to noticing that the Prophet did not

punish the woman.

-

The Importance of Foreplay. Jabir bin Abdullah narrates:

When I got married, Allah's Apostle said to

me, "What type of lady have you married?"

I replied, "I have married a matron."

He said, "Why, don't you have a liking for

the virgins and for fondling them? Jabir also said:

Allah's Apostle said, "Why didn't you marry

a young girl so that you might play with her and

she plays with you?" (Al-Boukhari)

Rights and Duties in Sexual

Relations

All scholars indicate that the right to sexual enjoyment

is one of the rights of a wife (Omran, 1992). They

do not deny her right to sexual fulfilment. Sexual

fulfilment for women was understood to depend on the

completed act of intercourse, something which withdrawal

was not (Mussallam, 1978).

Accordingly, some scholars disallow

withdrawal without the consent of the wife as they

believe that it would interfere with her enjoyment

of the act.

However, these rights are balanced

by women's duties. Many Hadiths state that a woman

should not refuse her husband. The Prophet said: "If

a man invites his wife to sleep with him and she refuses

to come to him, then angels send their curses on her

till morning." Al Boukhari. Also, he said: "If

a woman spends the night deserting her husband's bed

[does not sleep with him], then the angels send their

curses on her till she comes back [to her husband]."

Al Boukhari.

Islam and Sexual Health

Islam forbids all acts which are believed to be harmful

to sexual health, such as castration, sex during menstruation,

and anal intercourse. It is believed that applying

these teachings will help in maintaining sexual health

and prevent sexually transmitted diseases including

HIV/AIDS.

Sex Outside Marriage: Islam forbids all types of sexual relations outside

marriage, whether premarital or extramarital. Islam

advocates a number of specific measures to reduce

the temptations that may lure one into such relationships.

-

The Prophet encourages all followers

(especially the youth) to get married if they can,

so that their natural desires are legitimately fulfilled:

"Whoever is able to marry, for that will help

him lower his gaze and guard his modesty (i.e. his

private parts from committing illegal sexual intercourse)."

Al Boukhari.

-

Polygamy is allowed by Islam

in a bid to reduce the number of unmarried women

in a society.

-

There are clear instructions

to women to cover themselves and to appear in a

modest way so as not to attract men.

-

Boys are not allowed to associate

with girls after puberty. This tends to limit the

boy/girl friend (dating) practice.

-

Alcohol consumption, parties,

dancing involving both sexes – practices and

settings which can lead to sexual relations outside

marriage - are forbidden.

-

Meetings between a man and a

woman where they are without other company is forbidden.

-

Islam restrains women from the

kind of speech which may stimulate sensual passion

- "If ye fear God, be not too complaisant of

speech, lest the man of unhealthy heart should not

lust after you." (Quran Sura 33:32). The restraint

also extends to posturing and the manner of walking

- "And let them not strike their feet together,

so as to discover their hidden ornaments" (Quran

Sura 24:31). Indecent exhibition is also prohibited

: "And that they display not their ornaments

except those which are external" (Quran Sura

24:31).

Furthermore, the Prophet instructs

his followers that they should have sexual intercourse

with their wives if they get excited according to

the following Hadith. Jaber narrates:

The Prophet said: "Verily

a woman comes near in the form of a devil, and goes

behind in the form of a devil. When one of you is

pleased with a woman and she falls unto his heart,

let him be inclined to his wife and have sexual

intercourse with her, because it drives away what

is in his mind." Al Boukhari.

Sex outside marriage is considered in Shari'a not

only as a sin but also as a crime which is punishable

under law.

Castration: The

Hadith indicates, as narrated by Sa'd bin Abi Waqqas

- Allah's Apostle forbade Uthman bin Maz'un to abstain

from marrying (and other pleasures) and if he had

allowed him, we would have gotten ourselves castrated..

Al Boukhari

Sex during Menstruation: Islam forbids sex during menstruation - Sura 2:222

-

They ask thee Concerning women's course*. Say:

They are a hurt and a pollution: so keep away from

women in their courses, and do not approach them until

they have purified themselves. Ye may approach them

as ordained for you by Allah For Allah loves those

who turn to Him constantly and He loves those who

keep themselves pure and clean." (*Course

literally means menstruation)

Anal Intercourse: As narrated by Khusaimah bin Sabet: The Prophet said:

Verily Allah is not ashamed of truth. Don't approach

women by their backs (anal intercourse). Al Boukhari.

Also, as narrated Abu Hurairah, the Prophet said:

“Cursed is he who goes to his wife by her back.”

Al Boukhari.

In summary, Islam gives women and

men the right to sexual health by forbidding all what

is believed to be harmful. In addition, it provides

them the right to sex education and sexual enjoyment.

However these rights are not to be practiced outside

of legal marital relations.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

A growing literature of social, and anthropological

studies shows that Islam is interpreted differently

in different countries and by different social groups.

Religion is not the only factor, although it is very

important, that determines social outcomes. Traditions,

customs, and geographical differences are other factors.

Moreover, Islamic texts are flexible and could be

adapted for all places and all times. Some of the

current theologians tend to quote from the classics,

even with regard to old medical opinions whose errors

have been brought to light and which have since been

superseded by other more scientifically-grounded ideas.

These factors could explain some of the gaps between

Islamic ideology, as expressed by the Quran and Hadith,

and the practices which are based on customs and traditions

but misinterpreted as grounded in Islam.

From the Islamic point of view,

two different positions on reproductive choice may

be taken. The more traditional position gives women

little freedom to make decisions that bear on reproduction.

The second argues that constraints on reproductive

choice that exist in some Muslim countries are not

inherently Islamic. Hey further argue that the egalitarian

elements in the sacred texts should be the guide to

a reinterpretation of the doctrine that would be fully

compatible with ideas of human rights and reproductive

choice.

Contraception rights in Islam have

been discussed in detail in many other publications

(see the work of Omran, 1992). The majority of these

authors indicate that Islam gives women absolute right

to contraception. However, there is a diversity of

opinions regarding the permanent methods (surgical

sterilisation).

Regarding abortion, there is consensus

among the theologians that abortion after 120 days

is not allowed except to save the life of a mother.

However, there is no unified position among Muslim

scholars on abortion before 120 days. All the schools

of thought agree that Islam gives women a right to

abortion when their lives are in danger in the case

of a high risk pregnancy. Also, some schools agree

on the right to early abortion in cases of health,

social, mental and economic problems. There is a clear

indication of the need to revise and unify the Islamic

laws regarding abortion in the context of recent advances

in medicine and technology.

Regarding sexuality, Islam gives

women the right to sexual health by discouraging all

that was believed to be harmful, such as anal intercourse

and sex during menstruation. Islam also gives women

the right to proper sex education and the right to

enjoy sex. However, all these rights should not be

practiced outside of marital relations.

Rereading of reproductive health

definition: Taking into cognisance the socio-cultural

dimensions of reproductive health, the international

definitions of reproductive health can be adapted

to make them acceptable to, and adoptable by Islamic

countries. The proposed adaptations are as follows:

Reproductive Health in Islam:

A Redefinition

Within the framework of Islamic teachings, reproductive

health implies the ability of women and men to live

from birth to death with reproductive choice, dignity

and, to be reasonably free of reproductive health

diseases and risks. In addition, the ability of a

married couple to enjoy marital sex without fear of

infection, unwanted pregnancy, or coercion; to regulate

fertility without risk of unpleasant or dangerous

side effects; to go safely through pregnancy and childbirth;

and to bear and to raise healthy children.

Ahmed R. A. Ragab. Dr. Ragab is the

Associate Professor of Reproductive Health, International

Islamic Center for Population Studies and Research

at Al-Azhar University, Egypt.

References

Ahmed L. (1992). Women and Gender in Islam.

New Haven Yale University Press.

Cook. R. J (1993). "International Human Rights

and Women’s Reproductive Health." Studies

in Family Planning, 24 (2) pp 73-86.

Freedman, L and Isaacs, S (1993).

"Human Rights and Reproductive Choice." Studies in Family Planning, 24 (1), pp 18-30.

Madkour, M. (1974). "Muslim

Outlook on Abortion and Sterilization." In the Proceeding of Islam and Family Planning Conference In Rabat Morocco. Dec. 1971. Vol II:263-86. IPPF,

Middle East and North Africa, Lebanon.

Mussallam, B (1978). Sex and

Society in Islam. Cambridge University, Cambridge,

London, New York.

Obermyer, C. (1994). "Reproductive

Choice in Islam: Gender and State in Iran and Tunisia." Studies in family Planning Vol (25), Jan-Feb,

1994. pp 41-51.

___________ (1992). "Islam,

women, and politics." In Population and Development

Review: 19 (1) pp 33-60.

Omran, A (1992). Family Planning

in the Legacy of Islam. UNFPA.

Rispler-Chaim, V, (1993): Islamic

Medical Ethics in the Twenties Century. E.J Brill,

Leiden, New York.

Serour, G. I (1998): Personal communication.

Weeks, J. (1988): "The Demography

of the Muslim Nations." In Population Bulletin 43 (4).

|