Demography, Sexuality and Sexual Behavior Research in Nigeria

|

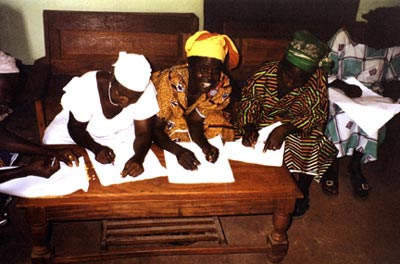

| Women from the

Akpamanya hamlet in the Nimbo community of Nigeria

engage in a health situation analysis activity

as a way to express their perceptions and experiences

related to women's health. Copyright © 2002 Serena Williams/CCP, Courtesy of Photoshare. |

INTRODUCTION

When HIV was first reported in1981, there was very

little concern that the disease will spread to Nigeria.

Nevertheless, there have been apprehensions about

the incidence and prevalence of sexually transmitted

disease long before the advent of HIV/AIDS. Despite

the near universal knowledge of STDs, earlier studies

on the incidence and prevalence of the disease were

clinically based. Hence research needs and the intervention

strategies were also clinically oriented.

Our earlier studies on the social

and behavior context of HIV/AIDS in Nigeria were undertaken

in the shadow of the AIDS epidemic in Nigeria on two

basic assumptions. The first was to increase social

science presence and research capacity available to

the AIDS epidemic. The second was to provide empirical

information that can assist in shaping possible intervention

and measuring their impact (Orubuloye et al, 1994).

These approaches were important because the major

protection available in much of sub-Saharan Africa

countries against HIV/AIDS, and probably most STDs,

in the foreseeable future, is sexual behaviour change.

Findings from research programmes

in Nigeria have shown that nearly every adult member

of the Nigeria society has heard of at least one type

of venereal disease, and know that it can be transmitted

by sexual relations. In one of the study about one-third

of all sexually active males and females reported

that they have been treated for a sexually transmitted

disease in their lifetime (Orubuloye, et al, 1994).

It is well recognized that many men and women will

eventually suffer from sexually transmitted disease

during the course of their active sexual life. It

is generally regarded as a form of social incompleteness

among the general population, if a sexually active

man had not experienced or had been treated for a

venereal disease in his sexually active life. Hence

venereal disease was not seen as posing a great danger

to society; hence little attention was devoted to

the social and behavioral context of the disease.

The situation has changed since

the AIDS epidemic began, especially with the evidence

that the disease is spread mainly through heterosexual

relations, and that STDs is a major co-factor in the

spread of HIV/AIDS.

It is now well recognized that in

many developing countries, a past history of STDs

is closely associated with AIDS. In sub Saharan Africa,

the proportion of AIDS patients with past history

of STDs varies from 35 percent in Tanzania to 50 percent

in Zaire (DRC). The figures range from 67 percent

in Rwanda to 75 percent in Zimbabwe, while the proportion

was as 71 percent in Haiti and 70 percent ion Martinique

(Pepin et al.1989). In Uganda, there is the evidence

that chancroid, syphilis and gonorrhea facilitate

the transmission of HIV (Berkley et al 1989). This

is partly because of the high prevalence of STDs in

the region, and mostly because of the growing importance

of STDs as co-factor in the spread of AIDS. Thus,

questions on the recognition of STDs symptoms are

now nested in general survey of sexual behaviors.

In STDs survey, respondents are

asked series of questions on the type of symptoms

experienced, whether and where treatment was sought,

type of treatment received and the outcome of such

treatment (Orubuloye, et al, 1994). In Nigeria, attempts

have also been made to study the health-seeking behavior

of STDs patients attending hospitals and health clinics

in an urban area of Southwest Nigeria (Akinnawo and

Oguntimehin, 1995)

These studies are aimed at developing

appropriate intervention strategies that will facilitate

the treatment of STDs patients and stem the spread

of the disease.

The first case of AIDS in Nigeria,

involving a sexually active thirteen year- old girl

was officially reported in 1984 (Nigeria, 1992). Subsequent

cases were found among commercial sex workers at the

major nodes of transport and commerce: Lagos, Ibadan,

Calabar, Enugu and Maiduguri. The initial reaction

to the epidemic was negative. Most people believed

that the disease originated from foreigners who brought

it to the women in the industry. It was also general

believed that the only way to avoid the disease was

to refuse contact with Europeans and the women working

in the sex industry. By 1991, HIV- positive truck

drivers were detected and concern arose in the industry

and among the general population.

The situation has change. AIDS has

now been detected in all segments of the Nigerian

population. Since the enthronement of democratic government

in May 1999 attention has focus on the AIDS epidemic.

The economic difficulties and political instability

of the last decade have largely drawn the attention

of government away from the AIDS epidemic.

The Nigeria 1999 sentinel survey

indicated that about 5.4 percent of the Nigerian population

may well be HIV positive. This translates to about

2.6 million people that are likely infected with HIV.

The year 2001 sentinel survey indicated a 5.8 percent

level of HIV positive cases in the country. These

figures are staggering and among the highest in sub

–Sahara Africa. In sub-Sahara Africa, the AIDS

epidemic has been identified as a heterosexual epidemic

and the degree of sexual networking (relations with

partners) has been confirmed to influence the level

of the disease, earlier researches were focused on

the determination of the degree and nature of sexual

networking. Research effort was first concentrated

on the general population and subsequent efforts focused

on high-risk groups and men’s sexual behavior.

SEXUAL BEHAVIOR AND SEXUAL

NETWORKING AMONG THE GENERAL POPULATION

In sub- Sahara Africa, sexual activity is defined

by social and economic context and cultural sanctions

and taboos exact behaviors to maintain the structures

of power, and there are taboos against discussing

sex with men of different generations, or in public

or with the opposite sex (Middle 1997 4:67). The AIDS

epidemic has gradually unraveled the mystery surrounding

sexuality. Men and women are equally at risk of begin

infected with HIV, with nearly 80percent of the risk

attributable to heterosexual transmission.

The nature and structure of the

African family system are important determinants of

patterns of sexual relations within and outside marriage

(Orubuloye et al 1997). Polygyny meant substantial

delay of male first marriage, and produces a situation

where half of adult males are single and sexually

active. It has also taught men that relations with

only one woman are not part of man’s nature.

Postpartum abstinence and low level of contractception

make the majority of women unavailable for sex for

a considerable of their reproductive life span.

An intensive study of multi-partnered

sexual relations undertaken in 1989 in the Ekiti District

(now Ekiti State) in Southwest Nigeria found that

three-quarters of single males, slightly more than

half of monogamously married males and a little over

a quarter of polygynously married males had extra-marital

sexual relations during the previous year (Orubuloye,

Caldwell and Caldwell 1991). The single and polygynously

married women reported high level of participation

in extra-marital relationships; nevertheless they

are more discreet in such relationships than their

male counterparts. Subsequently, a study of male sexual

behavior and its social and ideational; context was

carried out. It aimed at finding out the attitudes

of men and women toward men’s need for more

than one woman. It also investigated whether men are

thought to be biological different from women in need

for sexual variety, as well as reporting on men’s

actual sexual behavior and their wives’ reaction

to it.

Studies have indicated that women

are much likely than a man to believe that one woman

is sufficient for a man over a lifetime (Orubuloye

et al, 1991). This was especially the case among women

in monogamous unions than those in polygynous marriages.

Most women in polygynous marriages tend to start their

marital life in monogamous relationships and latter

end up in polygynous union as their husbands acquired

more wives. In traditional society most married women

believed that as the circumstance of their husband

changes, he is likely to acquire more women. Most

women look up to this as an inevitatable event in

their lifetime, and some may assist or encourage their

husbands towards this. Most women in the rural area

and the less educated one in the urban areas with

grown up children are not obsessed with their husbands

acquiring additional wives. Women in is situation

would welcome additional women as a co- wife than

the husband keeping girl friends outside. Once this

happens, the status of the woman changes and she becomes

less responsible to the man. Her attention will shift

to her children. Educated women and Christian are

far more likely to believed in insist on sexual monogamy,

and they are far more likely to succeed than the less

educated woman. Islamic religion considers extramarital

relations that do not end up in marriage as adultery

but approves of polygyny provided the man can make

adequate provision for the women and love them equally.

Men and women who believed that men will seek multiple

female partners explains this in terms of men’s’

fundamental nature and the culture, while Christians

see monogamous relationship as the Christian way of

life proclaimed in the Bible and preached in the Gospel.

Although Christianity preaches monogamy, it is flexible

on matter relating to multiple partnership and adultery.

Men who have more than one wife, and men and women

who engage in extramarital relationships may be denied

taking part in sacred activities such as the Holy

communion, they are less likely to be sent away from

the church on primarily because of sudden sexual urges

and the need for variety of sexual partners. The proportion

of men in this category was nevertheless below that

of those who believe that they can confine themselves

to one woman in their lifetime.

Because a range of social and economic

factors facilitates men’s extramarital sexual

transgressions, the control by their partners has

been difficult. Most husbands and wives do not eat;

sleeps go out together, and maintain a common budget.

Therefore there is no control of what men do with

their income, women are not expected to know or concern

themselves with this. In polygynous households, women

are not supposed to notice their husbands ‘

sexual activities or feel jealous about them; primarily

because their coming into the households derives from

such relationships in first instance. Most men believe

or pretend that their wives have no knowledge of their

extramarital affairs.

Although nearly all women with straying

husbands were aware that something was going on, they

often say nothing because both their husbands and

the society would detest their behavior. Nevertheless,

the more educated and Christian wives have most faith

in their husbands, and they are far more likely to

control their husbands’ sexual behavior and

complaint if their husband were leading a profligate

lifestyle. The majority of complaints were that the

men would become infected with sexual transmitted

disease or would bring disease, especially gonorrhea,

into the marriage. With the AIDS epidemic well underway,

majority of urban women believed that men could be

induced to confine their sexuality to marriage. This

is a dream not yet shared by the majority of men.

Most rural women believed and agreed that men often

need more than one wife, partly because polygyny is

part of the culture and mostly because of the need

for adequate farm labor force. In real life situation

the potentials of such labor force are no longer being

realized because of the jealousy and acrimonies that

now surround polygynous marriages. In rural life complaints

about men sexually straying are not just the business

of husband and wife but all of the relatives surrounding

them. Women in the rural area are often the scapegoat

if they press their complaints too hard. The phenomenon

of outside wife, a new variant of polygyny, is real

even among the high-educated urban middle class in

society (Karanja 1987).

Bigamy, the act of marring a second

time when one is already legally married, is also

not new. Although the act is an offence under the

marriage Act, women whose husband are involved in

this act seldom prosecute them for fear of bringing

shame to the family. Most women tend to leave with

the situation, while some opt for dissolution of their

marriage without pressing for damages against the

husbands, and may subsequently retain the name of

their husband. Certainly wives tradition have little

control over their husbands’ extramarital sexual

relationships; they are far more likely to try to

control their sons’ sexual activity or to see

that it is conducted in safety or that it does not

result in making girls pregnant. There are community

sanctions on wives monitoring their husbands’

behavior; there appear not to be parallel sanctions

on mothers watching their sons ‘sexual behavior.

Nevertheless, mothers consider monitoring their sons’

sexual behavior as their moral rights and social obligations

to them. In contrast the community experts mother

to monitor their daughters’ sexual behavior

and there are sanctions for failure to do so. Most

parents have the fear of their daughters’ becoming

pregnant before finishing at school; hence mothers

to enforce premarital chastity on their daughters

while their sons’ are given some degree of sexual

freedom.

Traditional society continues to

have a story influence on contemporary society and

its mores. Traditional religion did not impose sanction

on male and female extramarital and non-marital sexuality.

Discreet sexual access to women was allowed or tolerated.

Young wives often continued the relations they had

enjoy with men before marriage, and widows or separated

women maintained relationships with men for economic

reasons. The advent Christianity in the 19th century

had had some impact on the traditional sexual system.

The elites and women more widely, were attracted by

western compassionate marriage usually identified

as Christian marriage. The new religion preaches monogamy,

companionship and sexual fidelity. But it appears

that the majority of the followers have not taken

the messages very seriously. The level and intensity

of polygyny, and extramarital sexual may have declined

among the educated elites; they have not been eliminated

completely. Educated men and women are far more likely

to be more discreet about their extramarital sexual

transgressions than their less educated counterparts.

Educated women are far more likely to refused sex

to their infected or philandering husbands than the

less educated ones who lack the knowledge or the opportunity

to identify infection in their husbands. The African

sexual system has by and large passed through three

phases: the traditional system which allowed very

considerable sexual freedom for males and more discreet

freedom for females in certain circumstances; the

colonial and post-colonial system with its monetization,

urbanization and greater mobility of male and female,

and a new phase characterized by a major epidemic

in human history. Experience elsewhere has shown that

the AIDS epidemic is likely to lead behavioral modification.

The situation in Nigeria has not indicated a significant

change in multi- partner relationships. The situation

may change as the AIDS epidemic intensifies. Presently

only a few are really afraid of the disease and resistance

to the epidemic even among the high-risk population

is at present too low. Many people are pre-occupied

with the problem of the economy, while only a few

are apprehensive of the dangers pose by their sexual

behavior. Nevertheless the control of male sexuality

is important and may be an essential antidote for

stemming the spread of the epidemic.

There is now some evidence of changed

sexual behavior from countries that have witnessed

a high level of the epidemic but it will take some

time before this is realized in many parts of Africa,

and the death toll would have certainly been unprecedented

in history of epidemics. Before the advent of the

AIDS epidemic, there was very limited research on

sexuality and sexual relations from which to draw

upon. Earlier social science researchers were reluctant

to investigated sexual relations because of the sensitivity

of the topic and the fear of hurting the respondents,

and thus jeopardizing future social science research.

Because most of the earlier studies were on fertility,

infertility and family planning, researchers did not

possess the armonury of methodogies and body of knowledge

existing in other areas of social science research

when the AIDS epidemic struck. Because of the nature

and intensity of the epidemic, AIDS research has proved

in practice to differ from fertility and family planning

research than originally envisaged. There is substantial

premarital and extramarital sexual activity in much

of sub-Sahara Africa, and yet it is usually not widely

discussed and interviewers may be misinformed or refuse

information. There was and largely still is, extreme

reluctance to discuss sexual activity even within

groups where it is widely practiced. The issue of

sensitivity to providing information on matters that

are essentially private is therefore central to the

investigation of sexual relations outside marriage.

Initial research efforts in Nigeria and subsequent

ones were aimed at finding out the age at first sexual

intercourse, how many different sexual partners respondents

had both inside and outside marriage and how such

relationships were distributed over time. Descriptive

data were collected both on male and female respondents

and on different sexual partners.

Subsequent research attempted to

identify sexual partners and investigate perceived

sexual needs and male sexual behavior in greater details.

The surveys were often carried first by approaching

community leaders, the chiefs and other influential

people to convince them of the importance and the

need for the studies. Soliciting their cooperation

for the studies of the measures taken to ensure the

complete confidentiality of the studies and the materials

gathered. It was also an important means to allay

the fears and apprehensions of the respondents who

were not used to being asked question about affairs

that take place in private. Interviewers were often

from the same sub-ethnic group but not necessarily

from the immediate area, and were recognized when

visiting a household and all its members and neighbors

were aware of just what was taking place. Respondents

and their partners were not personally identified

in the sense of their names and addresses so as not

to damage the interview with refusals and deceitful

answers, and to avoid unwarranted invasion of their

privacy. Supervisors were employed mainly to check

with the interviewers the location of the sampled

household and their complete schedules, and to discuss

problems as they arose and the need for further interviewing.

Close supervision was necessary so as to avoid slippages

that could affect the quality and reliability of the

information gathered.

Although the response rate and the

quality of the data were high, there were some difficulties.

Women tended to understate their non-marital relations,

while men tended to overstate their, and there was

more understatement in rural than urban areas. There

was the difficulty of separating essentially commercial

sex from less commercial relations especially among

urban respondents where extramarital sexual relations

involve a high degree of financial and material support.

PERCEIVED MALE SEXUAL NEED

In sub-Sahara Africa, there is near-universal testimony

that, except in some prostitution, the male normally

takes the initiative for sexual activity. Studies

have also shown that men have unlimited sexual freedom

in and out of marriage, and that a man can be the

husband of several wives. This has raised the question

of perceived male sexual needs, by both men and women,

and the assumed basis of for these needs. An investigation,

which aimed at exploring the extent to which such

perceptions represent the situation in Nigeria, was

considered necessary. This was important for placing

male sexual behavior in the context of the society’s

social structure and belief systems, as well as suggesting

the possibility of change.

In order to achieve the objectives

of the study both male and female were surveyed on

their perception of male sexuality and asexual behavior.

A random sample of male and females over 15 years

of age was drawn in both urban and rural areas. Where

possible the sample was restricted to the same ethnic

group. Separate but related questionnaires were administered

to the male and female respondents; they contained

some common questions, which allowed lengthy answer

for subsequent study. Both young and old male and

female interviewers were engaged: each interviewed

only respondents of their own sex, and older interviewers

interviewed the older respondents. The interviewers

were paired so that both the husband and wife who

fell into the sample could be interviewed at the same

time. This strategy was important to secure accurate

information from women devoid of the influence of

their husbands.

Although the response rate high,

at least one or two callbacks were necessary in major

urban areas, after which any respondent not found

replaced with another one. Our original plan was to

limit the study to the major ethnic group in the region,

but because of a major political crisis on at the

time of the investigation all ethnic groups found

in the sample area were included. Nevertheless, more

than four-fifths of the respondents came from the

dominant ethnic group in Southwest Nigeria where the

research was undertaken, thus making it possible to

understand a single and dominant culture in what was

a cultural investigation. The methodological approaches

adopted in the study of male sexuality made it possible

for our understanding that wives have little control

over their husband’s extramarital relationships.

There was substantial evidence that the Nigeria system

of extramarital sexual relations, double less the

whole sub-Sahara Africa, operates as it dose, not

much because most of the society think that the male

need for sexual diversity is uncontrolled, but because

of the general perception that wives have no right

to comment upon or take notice of their philandering

husbands. Nevertheless, the study established a basis

for change in male sexual behavior as central to the

curtailment of the epidemic.

CONTROL OF FEMALE SEXUALITY

Attitude towards female sexuality varies across Africa,

among ethnic and religious groups. Some ethnic and

religious group suppresses and closets its women and

are punitive in their pursuit of even female sexual

extramarital affairs, in some women have some degree

of freedom and equality with men. Heterosexual transmission

of the disease is dominant in sub-Sahara Africa, and

the greater majority of all the HIV-positive women

in the world are found in this region. It is now clear

that their partners have infected the majority of

HIV seropositive women in Africa. This has been the

case with STDs. Therefore understanding female sexuality

and the extent to which they have control over it

are important for the dynamics of the epidemic and

the intervention strategies for mitigating its spread.

Before the AIDS epidemic broke very

little research was done on women’s control

over their sexuality in Africa, and the general assumption

was that the husband has right to his wife’s

person, and that most women in Africa were helpless

about changing their social situation. Events of the

last decade have clearly indicated that the situation

is changing. A survey of women in the era of AIDS

in Zaire did indicated that an increasing number of

number of women reported that they would stay with

a sero-positive husband to care for him but would

refuse to have sex with him or sharer the same bed.

This is a major departure from traditionally suppresses

and closets its women.

Studies from West African where

women have traditionally enjoyed some degree of autonomy

clearly shed some lights on the matter. Writing on

Ghana in 1931 Cardinal (1931:169) observed that the

status of women in the native household is equal to

that of the man and women do not hesitate to assert

their liberty. In this society it is believed that

women might have exercised their rights within marriage,

especially when there was conflict of interest (Awusabo-Asare

et.ai.1993).

In West Africa, the subsistence

economy is based on a division of labor by sex and

age. Women have traditionally traded and done household

work, they also have their own budgets, control resources

and make decision based on these resources. Although

marriage confers on a husband exclusive sexual right,

thecultutre has long expected women to have some control

over their bodies during certain periods in their

life-cycle: during menstruation and the postpartum

period, and after becoming a grandmother or reaching

menopause. Although the total period may have shrunk

in the last few years because of modernization and

increased use of contraceptives, twenty-five years

ago the duration of these events accounted for 60percent

of a women’s time between menarche and, menopause.

It was the responsibility and right of women to defend

these periods and the community sanctioned men women

who deliberately broke these traditional practices.

In 1990 study of women in the Ekiti

district of Southwest Nigeria (Orubuloye et. Al 1993),

nearly all women reported that they had refused sex

to their partners at least on one occasion in recent

times for a wide range of reasons. These include the

traditional forbidden period (menstruation, postpartum

abstinence and too soon after birth). Others include

punishment for bad behavior, quarreling, drunkenness,

sickness, wives’ right of choice and when the

partner has an infection. A significant proportion

of women reported that their partners were hostile

for refusing sexual advances from them, while some

turned to other wife or went out to other women, and

some accepted the situation calmly and regarded it

as inevitable. Domestic violence is rarely used to

resolve a matter of this nature; the men can turn

to other women, while the women can return to their

paternal homes temporarily. Divorce is not usually

an option.

Reactions of women to infected partners

present a different scenario. Nearly all the women

identified gonorrhea as their partner’s type

of infection. Many women were not aware of their partners’

infection because to a very considerable extent they

live separate lives with sexual intimacy at night

under poor illumination, and women often know little

about where and when their husband urinate. Nevertheless

a significant proportion of women who knew about their

partners’ infection refuse sex to them until

they underwent treatment, while only a few continued

sexual activities but with condoms suggested by partners

or insisted on by the women. Most Yoruba women are

able exercise this right because of the support they

will receive from the community, their family members

and because of their economic independence.

A significant proportion of Yoruba

women believe that they can refuse sex with infected

partners’ and only a few would continue sex

with condoms. Although a significant proportion of

women knew about condoms and had used them before

or currently using them, majority was not convinced

that condoms would guarantee against infection. Many

women have aversion to condoms and all contraceptives

as well. While many believe that condoms are too thin

to offer protection against sexually transmitted diseases,

other are apprehensive about the effects on other

contraceptives, especially the assumed reproductive

impairment. These are genuine reasons in a society

where there is little emphasis on sexual pleasure

and where emphasis is on high level of reproduction.

The among the major ethnic groups

in Ghana is similar to that of the Yoruba of Nigeria.

A 1991 study on women’s control over their sexuality

reveals that majority of women (60%) felt that a women

had the right to refuse sex with a partner who is

promiscuous, and 90% of women would do so when the

husband is disease; for fear of infection. More than

one half of the women had actually refused sex with

a husband on at least on one occasion on account of

jealously and to attract attention to themselves.

Among women whose partners had STDs, half had unprotected

sex, partly because of the belief that they could

not be infected and partly because of the misconception

that having sex with an infected person could cure

the disease. This poses a danger if extended to AIDS

cases (Awusabo-Asare et al 1993).

In Eastern and Southern Africa,

women are at a relatively greater economic and decision-making

disadvantage to their husbands than is the case many

parts of West Africa. In this region, as evident in

Uganda (Ssekiboobo 1992), and in Kenya (Muange 1998),

women are seen primarily as farmers with only very

limited access to urban trading and on physical separation

of what they themselves produce from that of their

husbands. Wives ‘ inability to refuse husbands

sex, insist on safe with them or force them to curtail

their extramarital sexual relations is an indication

their powerlessness. Women in this region compared

to those in West Africa are constantly oppressed by

a society in which they so finally break ties on marriage

with their families of origin that they are not welcome

back as a matter of right after a separation from

their husbands. They cannot demand access to farming

land on their return, and neither their own families

nor those of their husbands will expect them to bring

their children. The women’s refusal of sex would

be highly likely lead to divorce and to the loss of

access to the resources that her marriage had provided.

Women seemed relatively defenseless against their

partners if infected with sexual transmitted disease

or HIV.

A wide range of factors, which are

external to women, often influences sub-Sahara African

women’s ability or inability to control their

sexuality. The economic difficulties of the few years

meant economic insecurity and increased dependence

of women on their husband for support to them and

their children; women are therefore under pressure

to remain in unions that pose great danger to their

lives. The fear of losing the partner and the pressure

of the family members to remain in a union that poses

danger to the woman have become important more than

before. The assistance from the family to the relatively

poor members has shrunk to an all time low because

of the current economic difficulties. This may compound

the epidemic situation, as many young women across

the region have now taken to commercial sex to generate

income for their survival. Investigation reveals that

many of those women return to their place of origin

when they fall sick and subsequently infected men

who latter infect their partners.

Nevertheless, women need support

from the community and possibly from government to

be able to refuse sex from partners who are leading

dangerous sexual lives or infected with HIV. Women

must be convinced that although this may not be culturally

acceptable but it is morally justified.

STUDYING HIGH-RISK GROUPS

Female Commercial Sex Workers

Our first attempt at studying people in high-risk

occupations was that of female commercial sex workers.

In much of sub-Sahara Africa, there is a substantial

male demon for sex outside marriage, and this has

led the growth of commercial sex industry in the region.

The growth of the commercial sex industry has long

exposed and many women employed in it and their clients

to increased risk of sexually transmitted diseases,

and in the last one decade presents the danger of

infection with HIV/AIDS. Opinions tend to converge

regarding the origin, nature and causes of commercial

sex in Africa. In a recent publication, pellow (1997)

wrote that prostitution has been prevalent and visible

in Africa cities since the nineteenth century, rooted

in the colonial past and poverty; a way in which women

have used and manipulated their sexuality because

they have been denied active participation in the

economy. Writing on the Hausa Muslim w omen of Northern

Nigeria, where according to pellow, marriage is normative

but rarely stable, women become prostitutes out of

economic need because they do not want to be married,

and prostitution provides an alternative lifestyle

(p.70). in a similar vain white (1997) wrote that:

prostitution in Africa like prostitution anywhere

else is not a form of social pathology or cultural

predisposition. She also went further that it is one

of the ways women’s work supports their families

and that the ways women in Africa has prostituted

themselves have to do with the kinds of families they

are supporting and creating, and the kinds of support

their families required at that time.

Pittin (1983) discussing the house

of women in Katsina in Nigeria, observed that there

are houses that accommodate women on their own, who

support themselves completely or in part by selling

their sexual services. Oppong (1983) identified and

reported on a group of white-collar women in Accra

Ghana whom she described as single wealthy and potentially

mobile, who chose to content themselves with the steady

improvement of their economic resources and enhancement

of theirs bargaining positions by exchanging sex for

money. In Gambia, the economic incentives were powerful

motivations to prostitution (Pickering et al.1992).

The economic difficulties faced

by many of the Africa countries since the early 1980s

have resulted in the growth of commercial industry.

Many poor families encourage their young girls to

migrate to the major towns and commercial centers

for wage employment, which is not easy to come by

quickly thereby putting pressure on them to go into

commercial sex. The movement to the major towns and

commercial centers was facilitated by the rapid growth

of the educational system and of the transport network.

The growth of the commercial sex industry has longed

exposed many women in it as well as their clients,

to increased risk of sexually transmitted diseases,

which were know to affect one third of the population,

and now presents the danger of infection with HIV/AIDS.

Over two-thirds of all the people now living with

HIV in the world –nearly 21million men, women

and children are reported living in sub-Saharan Africa

the home of 9percent of the worlds population (UNAIDS1998).since

the advent of the epidemic, HIV in sub-Sahara Africa

has mostly spread through sex between men and women

and the commercial sex industry and the people working

in it have played a major role in the course of the

epidemic.

Across sub-Saharan Africa, prostitution

takes place in large towns or cities where there is

demand for it. The majority of sex workers work in

places where alcohol i9s sold and where dancing is

also a common feature. The young women in the trade

live a more restricted and institutional life in the

place where they work. They isolate themselves to

retain their anonymity and maintain close contact

with their hometown by sending money regularly to

their family and where they plan to return at the

end of their sojourn in the city (Orubuloye,et al.1994).

Nowadays the sex workers are young,

mostly single less than30 years of age, better educated

and do not seem to stay a lifetime in the trade. The

majority of the young women now in the trade appear

to have no real occupation between leaving school

and taking up prostitution, and the unemployment situation

has driven many to seek alternative jobs. Prostitution

for this new generation of sex workers is an opportunity

for intensive savings, in order to establish themselves

in small business for the rest of their lives. Nearly

all the women in commercial sex trade do make substantial

savings beyond their remittances, expenditure on health,

cosmetics, and deductions for board and food. Prostitution

guarantees an income level higher than what people

of the same qualification earn in government employment.

Many sex workers tend to remain

anonymous, and there are no great disabilities connected

with profession. Most keep contact with their relatives

and many relatives probably have some ideas of what

the young women are doing for a living in the city.

Many return to their homeland at the end of their

sojourn in the city to establish businesses and lead

respectable lives for the rest of their lives. In

addition, those who had retired from the business

provide necessary information for young recruits into

it, and sometimes act as recruitment agents for the

managers of hotels, brothels and bars in the cities.

There are no clear socio-economic

groups from which the sex workers come. They are likely

to come from both urban and rural areas as well as

from all the ethnic groups in a country. A significant

aspect of commercial sex in recent years is the spread

across international boundaries, and the trade is

almost synonymous with migration. Commercial sex workers

are highly mobile, so are their clients. It is also

unique that most of the sex workers do not practice

their trade among their ethnic groups or where they

can easily be recognized. Most sex workers see the

trade as a stage in life and an investment for later

life, and inability to make a substantial saving leave

them in the profession for a considerable length of

time.

The AIDS epidemic has raised the

issue o f safe sex for the sex workers and their clients.

A significant number of the sex workers had adequate

knowledge of condom and the potential effects on minimizing

the infection of HIV. Sex workers had effectively

used condoms as protection against STDs and pregnancy,

and about one-third of those in the cities now attempt

to use condoms regularly, while over one half now

regularly suggest the use to their customers. Trust

in the condom has significantly increased among sex

workers and their clients a situation, which can largely

be attributed to the massive campaign currently going

on and the regular supply condoms. Nevertheless, the

current economic difficulties and political instability

are jeopardizing the supply of cheap condoms. A significant

number of the clients of the sex workers who normally

provide condoms during sexual encounter are no longer

able to afford them. Many are now willing to trade

in free condoms for cash to pay the sex workers. This

may well pose a serious danger of the spread of AIDS

and other sexually transmitted disease to the sex

workers, their clients and the general population.

The sex workers and their clients

are now sufficiently aware of AIDS, as has been the

case for STDs for generations. They would be receptive

to any organized program to combat them. Nevertheless,

neither the AIDS epidemic, nor the government information

program has done anything to reduce the flow of young

and attractive women and their clients into the trade

or to alter its essential nature. The economic difficulties

faced by many families and the high level of unemployment

among high school graduates that now dominant the

trade may continue to guarantee the supply of new

comers into it. Increased supply and promotion of

highly subsidized condoms will be a critical factor

in slowing or halting the AIDS epidemic. Government

legislation against prostitution or constant police

raids on sex workers cannot provide a quick solution

to the dangers posed by those involved in the trade

and the general population around them. The study

of commercial sex workers in the hotels, bars and

brothel entails a different methodologically approach

from the study of the general population. In the study

of rural and small towns in Southern Nigeria, the

number of institutions and the sex workers was small

hence all the institutions and the sex workers were

included in the sample. Whereas in the large urban

centers and cities, the number of institution was

so great that they had to be sample and then appropriate

weighting was achieved within establishment by interviewing

a fixed proportion of the young women working in the

sex industry. The cooperation of the managers was

secured before gaining access to the women and young

male interviewers who agreed to pose as potential

customers were employed to interview them. Cigarettes

and drinks were provide and in a substantial number

of cases the interviews were completed only by additionally

making a payment for time lost as a result of the

interview. This was the only way to gain the total

support of the sex workers whose chief aim was to

maximize earnings in a very highly competitive trade.

The approach yielded a robust type of sample but excluded

a substantial number of the high-class prostitutes

who solicit for customers in the street and around

the hotels.

In the Northern Muslim area the

approach was different, more of the commercial sexual

activity is unconnected to institutions, and a substantial

numbers of sex workers who are from Southern Nigeria

roam around the major hotels and streets in the major

cities soliciting for customers every night. Matured

women health workers who succeeded in gaining interviews

by emphasizing their concern with sex workers’

health interviewed many of these street prostitutes

in a snowball kind of sample. The introduction of

stiff laws and penalties in the Muslim regions of

Nigeria is likely to drive the sex workers under ground

and make it a well nigh impossible task to identify

and study them.

A recent project focused on interventions

among the sex workers in Ado-Ekiti, a process that

was rendered easy by our previous contact with them

and their managers. A one-day seminar was first organized

in one of the hotels for all the sex workers and their

managers working in the town. The seminar aimed at

educating the sex workers and the manager about sexually

transmitted diseases including HIV/AIDS and the need

to protect the sex workers against being infected

by their clients or they infecting their clients.

Condoms were distributed free at the end of the meeting,

and subsequently fortnight for a period of six months

during which records of use and problems associated

with it were identified and solutions found to them.

The project has increased the use of condoms by the

sex workers and their clients, and many sex workers

are now able to refuse sex with clients who refuse

condom, and many clients now bring their own condom.

Nearly all the young women who engage in commercial

sex go the city to make quick money, and most intending

to stay only long enough to make enough money to set

themselves up in business back home and to secure

a good marriage and become respectable members of

their communities. This raises a difficult survey

methodological question, for most intend to go back

home and make on mention of their actual occupation

to their families and future husbands. This will pose

a serious methodological problem of identification

in any attempt to survey this will group of people

as has successful been done in the case of return

labor migrants.

Truck Drivers

Across Africa, long-distance haulage drivers play

important role in the economies of the countries.

Similarly the drivers are a major source of STD and

now HIV/AIDS infection and the levels of disease are

considerably higher along they ply frequently. The

research project undertaken in the early stage of

the epidemic aimed at investigating and identifying

those aspects of the drives’ behavior and way

of life that made them vulnerable to infection and

thus pose dangers to themselves, their wives and the

society. A major methodological obstacle arose from

the mobility of the drivers. In order to overcome

this interview were conducted at highway truck stops

along the major highway that run from the Southwest

part to the Northwest of Nigeria where the drivers

stop for meals, serviced or repair their truck, sleep

and have sex. The truck stops are large laces often

filled with huge trucks parked for half a mile, producing

a great deal of noise and movement as engines oil

and tyres are changed, and where mechanics and hawkers

are everywhere. The truck stops are often busy, rough,

tough and dangerous places. The fluid situation at

truck stops made it impossible to obtain a complete

listing of all drivers stopping there from which to

draw a sample. All drivers who stopped and willing

to be interviewed were interviewed.

It was more appropriate to use attractive

young ladies who are rarely seen in the truck stoops

and whom the drivers were willing to give some attention

to while doing other things and whom the drivers think

they can establish some kind of relation with. The

drivers soon discovered that most of them were university

undergraduate students who were less likely to accede

to their request. Because the drivers were always

in haste, the questions were short and were best to

memorize them as well as the answers and complete

the questionnaire later. The response rate was high

and the drivers who refused to be interviewed were

only those who were too busy to give up their time

to be interview or in haste to meet up with some specific

requirements of their employers.

A later project among truck drivers

included an intervention program preceded by a one-day

open seminar in one of the major lorry parks on safety

on the highway. The seminar was to sensitize the driver

to the dangers, which unprotected sex, can pose to

them and their wives in the course of their daily

activities. The intervention included demonstration

on proper use and distribution of condoms. Subsequent

follow-ups confirm a general rise in the use of condoms

among the drivers, especially with sex workers itinerant

traders.

The great majority of African women

farm or trade. Most of the trading is in raw foodstuffs;

cooked food, textiles, palm oil, kola and groundnuts,

cooking utensils, jewelry and a wide range of other

locally manufactured and import goods. In the rural

areas, most trading activities are in front of the

houses or from house to house or in the markets on

every fives days. In urban areas, most trading is

far more likely to take place far away from the usual

place of residence of the traders. Most girls have

traditionally assisted their mother in hawking goods

from house to house or at market places. The advent

of motor vehicles created new market places at the

lorry parks or at the bus and truck stops along the

road. Female hawkers, who sell few items from portable

tray, from a fly- proof box made of glass and wood,

or from a temporarily erected stand, are common in

sub-Sahara Africa. The investments and returns in

this type of trading are usually small. Most of these

young women hope to have a small stall in the market

some day, perhaps capitalized by a future husband.

Investigation among the itinerant traders in Ibadan

shows that the majorities of the traders are usually

single, sexually experienced, practice contraception

and has multiple sexual partners. The goods they sell

range from cooked food items, ice water mineral drinks

to chewing gums, coconuts, sugar and kola nuts. These

are items that are often in high demand by drivers

and their passengers.

Because of the nature of the lorry

parks and bus stops, the drivers, bus maids and passengers

often regard young women who trade there as potential

sexual partners. They frequently make suggestive advances,

and the women often offer sex to them in return for

money or goods, to supplement their income and increase

their savings. Women who sell goods along the road

and in lorry parks have been identified as playing

a role in the spread of infection because of their

way of life. Many have multiple partners and have

sex with men who themselves often have sexual relations

with many women including sex workers. The young women

are becoming increasingly worried about the risks

posed by having sexual relations with many men now

that the campaign about STDs and AIDS has been extended

to the lorry parks, bus stops and the major highways

where the women trade. A significant number of them

had suffered from STD, usually gonorrhea, while nearly

all had heard of AIDS. The women are in a serious

danger because many of their sexual partners especially

the drivers assume that they are less likely to have

HIV because they are young, because many have had

little sexual experience and because they are less

likely to be full-time commercial sex workers. This

may become a major root for the spread of AIDS, as

has been the case for STD. The contribution of the

itinerant hawkers is important to the efficiency of

the transport system by selling a wide range of goods

at the windows of buses and trucks. The lorry parks

and the bus stops offer employment and provide income

for many families. The chance of the traders to make

a sale depends on maintaining good relationships with

the drivers, the bus maids, the porters and regular

passengers who dominate the transport system. Offering

sex is a way of developing acquaintance with drivers

or passengers. Some of the relationships often become

permanent and some of the young women may end up as

additional wives to the drivers. Because of the nature

of the young women educational campaigns about AIDS

and other STDs at the lorry parks and bus stops are

important for disseminating information to all those

who work to support the transport system as well as

those who work in it. Such campaign should aim at

changing sexual behavior and use of condoms. Unfortunately

the economic difficulties which most of the sub-Sahara

African countries are currently going through have

made it difficult for such campaign to have its desired

effect.

The sex workers and the truck drivers

are closely related to the young itinerant female

hawkers who sell goods in the lorry parks, truck stops

and from house to house. These women sell a few items

from portable tray frequently balanced on their heads,

from a fly-proof box made of glass and wood, or from

a temporarily erected stand in the lorry parks, truck

stops and along the highways. They sell goods that

are in high demand by the drivers and the passengers

as truck, buses and vans disgorge passengers or as

people wait for transport or trucks and buses slow

down during traffic hold ups. This is a common phenomenon

in West Africa. Because of the economic difficulties

now faced by many African countries and the high rate

of unemployment, a significant number of young males

has infiltrated into the trade that was an exclusive

preserver for the women. This often leads to stiff

competition and conflicts between men and women trading

in these areas. The young men tend to outwit the young

women when chasing their customers most of the young

women are unmarried, and in the past such women usually

assisted their mothers in trading. An increasing number

of young women are now selling on their own, and most

of them hope to have a stall in the market when they

get married. Because the lorry-parks, trucks stop

and the highways are rough and tough places, most

of the interviewers were males: the questions were

short and the interviews were conducted fairly rapidly

often by memorizing the question and answers. All

female hawkers in each lorry-park or truck stop were

identified in the records to avoid interviewing the

same women twice. The response rate was high and a

lure in traffic moment, usually in the mid-afternoons,

provided opportunity for more interactions between

the women and the interviewers.

SURVEY OF YOUNG PEOPLE 15-24

YEARS OLD

In 2002, the federal ministry of health carried out

a behavioral sentinel survey among 7902 young people

15-24 years old consisting of 3946 female in 14 states

in Nigeria. The survey describes the characteristics

of Nigerian young people spread across all geopolitical

zones and many ethnic groups with regards to their

sexual behavior, knowledge and attitude to HIV and

condoms use. Their profile is that of young people

aged 15-24 with a mean age of 19.1 years and a high

level of education. Only 0.5% lacked formal schooling

while more than 57%had attained secondary education

and majority (83%) of whom were single. More young

people in the Northern Zones were married compared

to those in the Southern zones.

About one-half of all respondents

had had sexual experience. The median age at first

sexual experience was 17 years. However the females

than males had reported sexual experience in the last

12 months. The lowest rate of sexual activity was

reported in Jigawa State, which incidentally also

had the lowest HIV prevalence in the 2001 national

survey. The most common reason given for the first

sexual experience for females was the desire to have

children while that for the males was for fun. In

terms of age mixing, the disparity in age between

sex partners of male and female respondent ranged

from 1- over 20 years. For about two-thirds of all

respondents the range of age disparity was 1-9 years

and for about one0third it was 10years and over. About

one-fifth of the females had partners who were en

years and above older than them. Among the 3811 respondents

who were sexual experience 53.6% did so with regular

partners, 21.8%with casual partners and 17.6% had

engaged in transactional sex. By gender, 56% of all

male and 77% of all female respondents who were sexually

active within the last one month reported having only

one sex partner they considered as regular. For sex

partners considered as casual about 26% of male and

28% of female respondents sexually active admitted

to having sexual intercourse with at least one such

partner within the last one month. Those who admitted

to transactional sex with at least one partner within

the same period were 22%of the males and females who

admitted to transactional sex. Among male respondents

2.6% admitted to having sexual intercourse with males.

Multiple partnership and sexual intercourse with sex

workers and casual partners as well as men having

sex with men constitute risk sex behavior. It can

be inferred from these findings that a large proportion

of young people were involved in sexual activity involving

multiple partners and in relatively risk sexual practice.

This risk is greatest when the sexual intercourse

is unprotected with a condom.

The age at first sexual intercourse

is an important factor in the spread of HIV sexually

transmitted infections. It is also important as a

cause of teenage pregnancy. The younger the age the

more likely it is that such persons would be unable

to have enough information to protect them apart from

begin subject t to exploitation by older persons.

Young people are more likely to spend youthful time

at school and practice sex outside marriage. They

need information to protect them from begin infected.

Young people who use alcohol and drugs and engage

in multiple partners are at risk for HIV and other

sexually transmitted infections. So also are young

people who choose partners among those that may be

much older than them as such relationship may be transactional

and exploitative. The level of awareness of sexually

transmitted infections was generally high among both

male and females across the States. However, the level

of knowledge of STIs in men and women was general

poor. Knowledge of the specific signs and symptoms

of STI Between 20% and 33% of the respondent reported

that they knew specific signs and symptoms of STIs

in women compared to between 23% and 41% who reported

same for overall, 10% of the respondents reported

a genital discharge in the last 12 months and 3.6%reported

a sore or ulcer.

IDENTIFYING SEXUAL NETWORK

Perhaps to the most difficult aspect of the series

of our investigations on sexual networking was the

identifications of sexual partners and mapping sexual

networking conducted in Ondo Town in 1991. Research

on the subject is difficult and painstaking because

individuals are always reluctant to state the number

of sexual partners accurately, especially those that

are commercial sex. The original research described

sexual behavior and characteristics of individual.

Such information was by no means enough to provide

an adequate description of their sexual networks or

to determine the extent to which men’s sexual

activities are diffused through a considered part

of the society rather than focused on a small number

of women providing commercial se.

Earlier research had indicated that

men were more likely than women to disclose fair accurately

the extent of their sexual activities, and that men

would also provide more details than women about their

partner. Men were generally more aggressive than women

in seeking to identify their partners other partners,

primarily because men are more discreet about their

sexual behavior and that men believe that women should

keep to monogamously relationships than men. It was

also believe that men would suffer little or know

deprivation if their exmarital sexual affair becomes

public compared to women. Men could always argue that

they are seeking for another wife and the society

will approve of this explanation. Therefore it was

decided to interview men., and also important to carryout

the investigation in a relatively large urban location

where people are more open about sexual matters. The

obstacle was partly overcome by selecting an urban

area with a quarter of a million people, a place where

men were more discreet about sexual networking and

where there were substantial resources to support

it.

The methodological approach produced

a plausible result. Nearly all those men who reported

extramarital or non- marital sexual partners during

the year agreed to identify them. A significant proportion

of the partners was described as girlfriends or women

friends, fewer than one percent were described as

sex workers. The practicability of establishing how

many partners a man has the number and type of the

partner’s partners depends on the extent to

which the w hole sexual networking system is carried

out openly or surreptitiously. Despite the assumed

openness of the community selected for the investigation,

nine out of ten of all the married men currently having

extramarital relationships maintained that their wives

did not know of these liaisons. Traditionally wives

are not supposed to know or ask question about their

husbands’ extramarital affairs. With that extension

of western education to women and the movement towards

monogamous and companionship unions, women are increasingly

aware of their right to ask such questions from their

philandering husbands. Nevertheless, three- fifth

of the men reported that some of their relatives knew

of their extramarital sexual relations. This is a

common pattern across Africa, relations and friends

often know of other relatives and associates extramarital

affairs. Quite often they initiate and sustain such

relationships.

Identifying partners was more problematic.

Only a small fraction of the men could and willing

to accurately describe their extramarital partner’s

partners and the majority of the men could not be

bordered and would not participate in a sexual network

more complex than the ones they were in. the threat

that the men might break with partners they suspect

of having affairs with other men made those partners

conceal the existence of other men in their lives.

This often happens if a man suddenly discovers that

the woman he was going out with had another partner

or partners. Women are conscious of this and are apprehensive

of the risk that might jeopardize the support they

receive from their extramarital relationships provide

additional vital income for poor families, widows,

divorced or separated women, single girls seeking

support to stay in school or become established careers

and to married women whose husband cannot meet their

financial need and who choose to lead high profile

lives.

The research clearly showed that

it was a difficult task to identify partners’

partners even in a society that pride itself in the

openness of sexual matters. Attempts to do this may

cause severe damage to network of relationships and

impair future social science research. For a more

complete identification, a new form of methodology

will have to be invented. Perhaps it may be possible

to do this in a small community where everybody knows

one another, the type of relationships entered into

by individuals and where the research can successfully

conceal his identify.

OBSTACLES TO BEHAVIORAL

CHANGE IN THE PRESENCE OF AIDS

Earlier research reports on sexual behavior and sexual

network (Orubuloye et al. 1994) led us to believe

that their obstacles to behavioral changes is the

need to investigate an important aspect of the social

and behavioral context of the AIDS epidemic. In an

attempt to fill this gap a resistance, to change in

Sexual behavior Project was undertaken in 1998/99

to test the earlier propositions, ascertain current

situation and determine future trend.

Four research areas were selected

in Southwest Nigeria: Ado-Ekiti, the capital of Ekiti

State; Ibadan the capital of Oyo State; Badagry and

Ojoo two sub-urban areas in Lagos and Ugep a rural

district of cross river- State in Southeast Nigeria

(et al Orubuloye and Oguntimehin, 1999 and Caldwell

et al 1999).

The Ado- Ekiti research interview

all males who frequent the hotels and bars, which

offer commercial sex for a period of three months.

A household sample survey of adult male was conducted

in sexual affairs with more than one partner Ibadan,

Lagos and ugep. The survey yielded a total sample

of 1005 respondents; five more tan the anticipated

size of 1000 males. Questions were asked of the men

the number of their sexual partners over a period

of time attitude towards STDs/AIDS and death and use

condom. The refusal are was only one percent in Ugep,

typical of rural areas, five percent in Ibadan, ten

percent in Ado-Ekiti and 15percent in Lagos a busier

and less tolerant population.

The results were not different from

our previous investigations. Reported number of sexual

partners was high and many men were not ready to disclose

their sexual network of relationships beyond one or

two partners. A larger proportion of men is yet to

see the dangers inherent in their sexual behavior.

There was a general robust attitude

towards death and the majority accepted death as inevitable

and was willing to accommodate its timing. This a

major obstacle to sexual behavior change and may be

will a catalyst for the spread of the epidemic. An

AIDS epidemic is well underway in Nigeria the level

may well reach that of the East and southern African

epidemics. Nigeria has a large population yet a few

have had close contact with AIDS deaths primarily

because the epidemics started late. When it was established

that certain people died of AIDS friendly neighbor

and relatives are not told because of the shame that

may bed brought to the families of the affected people.

Very few Nigerians have been buried with the mourners

knowing for certain that the cause of death was AIDS.

The reality of the epidemic has not yet impacted on

the vast majority of the people, hence the denials

of the existence of the disease.

CONCLUSION

Researching sexuality, sexual behavior and multiple

sexual relationships has raised the central issue

of sensitivity to providing information on matters

that are generally considered to be private. Although,

there is a high level of premarital and extramarital

sexual activity in Nigeria, the practice is not usually

widely discussed and interviewers may be misinformed

or refused information. The knowledge that an investigation

is see king information within a community on multiple

sexual relations can cause excitement and a curiosity

about which person is begin interview. There was understatement

of sexual partners especially by rural females while

urban males tended to overstate theirs. On the contrary

men tended to understate their relations with sex

workers by describing them as friends. Nevertheless,

the evidence on the core data on sexual networks produced

a pattern that is internally consistent t and methodological

that is satisfactory and findings that can be trusted.

The HIV/AIDS epidemic has facilitated research on

sexuality and sexual behavior and earlier conception

that sexuality and sexual behavior cannot be studied

because of the sensitivity and that such investigation

would distort relations with respondents and damage

other inquiries has finally been put to rest.

By I. O. Orubuloye.

Dr. Orubuloye is a professor at Department of Sociology,

University of Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria.

References

Akinnawo, E.O and Oguntimehin F. 1995. "Health

seeking Behavior of STDs patients in an urban area

of Southwest Nigeria”: In I.O Ourbuloye, J.C.Caldwell,

Pat Caldwell and S. Jain Eds. The Third World AIDS

Epidemic Health Transition Review 5 (Supplement):

Canberra, Australian National University.

Anarfi, John K. and Kofi Awusabo-Asare,

1994. "Experimental research on sexual networking

in some selected areas of Ghana". PP29-44 in

I.O.Orubuloye, J.C. Caldwell, Pat Caldwell and Gigi

Santow, Sexual Networking and HIVAIDS in West

Africa: Behavioral Change and the Social Context.

Canberra, Australian National University.

Awusabo- Asare, Kofi, J.K Anarfi

and D.K. Agyeman. 1993. "Women’s control

over sexuality and the spread of STDs and HIV/AIDS

in Ghana." Health Transitional Review (Supplement) 3:1-6. Canberra, Australian National

University.

Backeley, S. F, Wildy W. Wirski

R okwara, S.I Downing R, Linman, M.J.White, K.E. and

Sempala, S. 1989."Risk factors Associated with

infection in Uganda". Journal of Infectious

Disease, 160, 1:22-30.

Caldwell John C.,et al, Supplement

to Health Transmitted Review 3. Canberra. The

Australian National University.

Caldwell Jon C., I.O Orbuloye and

Pat Caldwell. 1992a "Fertility decline in Africa:

A new type of transition?" Population and

Development Review 18,2:211-2423.

Caldwell John C., I.O.Orubuloye.

1993. "The nature and limits of the sub-Sahara

African AIDS epidemic: Evidence from geographical

and other patterns". Population and Development

Review 19, 4:817-848.

Cardinall, A.W. 1931, The Gold

Coast, 1931. Accra: Government printer.

Gun V.A. 1995, "Sexual networking

among the Hausa-Fulani of Borno State Nigeria"

Mimeograph, Department of sociology, University of

Maiduguri.

Isiugo-Abanihe Uche C. 1994. "Extramarital

relations and perception of HIV/AIDS in Nigeria". Health Transition Review. 4, 2:111-125.

Karanja, Wambui Wa. 1987."Outside

wives and inside wives' in Nigeria: a study of changing

perceptions in marriage." Pp247-261 in Transformations

of African Marriage, ed. David J Parkin and David

Nyamwaya. Manchester University press.

Larson A. 1989. “Social context

of human immune-deficiency virus transmission in Africa:

historical and cultural basis of central; African

sexual relations”. Review of Infectious

Diseases 11:716-731. Middleton, John. 1997. Encyclopedia

of Africa South of the Sahara. New York.

Scribers. Muange, V.M. 1998. "Sexual

Networking and Response to HIV/AIDS among the Luo

of Kisumu District, Kenya." Ph.D Thesis. Australian

National University Canberra. Nigeria, Federal Ministry

of Health and Social Services. 1992. Nigeria Bulletin

of Epidemiology, 2pp. 10-16.

Oppong, Christine. 1989. Female

and Male in West Africa. London: George Allen

and Unwin.

Orubuloye , I.O. 1981(a). "Abstinence

as a method of birth control: Fertility and child

Spacing practices among rural Yoruba Women of Nigeria."

Department of Demography, Australian National University.

Orubuloye, I.O. Jonh C. Caldwell

and Pat Caldwell.1991. "Sexual networking in

the Ekiti District of Nigeria". Studies in

Family Planning 22,2:61-73.

Orubuloye, I.O., John C. Caldwell

and Pat Caldwell. 1992. "Diffusion and focus

in sexual networking: Identifying partner and Partner." Studies in Family Planning 23, 6:343-351.

Orubuloye, I.O., Pat Caldwell and

John C. Caldwell, 1993a. "Africa Women's control

over their sexuality in an era of AIDS". Social

science and Medicine 37, 7: 850-872.

Orubuloye, I.O., John C. Caldwell

and Pat Caldwell 1993b. "The role of high-risk

occupation in the spread of AIDS: Truck drivers and

Itinerant market women in Nigeria". International

Family Planning Perspectives 19,2:43-48.

Orubuloye, I.O. Pat Caldwell and

John C. Caldwell. 1994. "Commercial sex workers

in Nigeria in the shadow of AIDS". Pp 101-116

in Sexual Networking and AIDS in Sub-Sahara Africa,

Behavioral Research and the Social Context ed.

I.O. Oyubuloye et al Health

Transition Series No4, Canberra: Australian National

University.

Orubuloye, I. O., John C. Caldwell,

Pat Caldwell and Gigi Santow. 1994. Ed. "Sexual

networking and AIDS in Sub-Sahara Africa: Behavioral

Research and the social context" Health Transition

Series No4, Canberra: Australian National University.

Orubuloye, I.O. John. Caldwell,

Pat Caldwell. 1995. "The cultural, social and

attitudinal context of male sexual behavior in urban

Southwest Nigeria." Health Transitions Review 52: 207-22.

Pepin J., Flumer, F.A.Brunham, R.c.Piot,

P, Cameron, D. W. and Ronald, A R.1989. "The

Interaction of HIV Infection and other Sexually Transmitted

Diseases: An opportunity for Intervention" Editorial

Review, AIDS 3, 1:3-9.

Ssekiboobo, A.M.N. 1992. Women's

social and reproductive rights in the age of AIDS

paper presented at workshop on AIDS and Society, Kampala,

15-16 December.

Pellow, Deborah. 1997. 'Sexuality'

pp. 65-70 in John Middleton, Encyclopedia of Africa

South of the Sahara. New York. Scriber.

Pickering, H. J. Todd, D. Dunn,

J pepin and A. Wilkins. 1992 "Prostitutes and

Their clients: a Gambian Survey." Social

Science and Medicine 34, 1: 75-88.

Pittin, Renne. 1983. "House

of women: a focus on alternative lifestyles in Katsina

city ‘pp291-302 in Female and Male in West

Africa. London; George Allen and Unwin.

White, Louise. 1997. 'Prostitution'

Pp 532-535 in John Middleton, Encyclopedia of

Africa South of the Sahara. New York. Scribers.

UNAIDS/WHO.1998. Report on the

Global AIDS Epidemic. Geneva.

|