Contradictions in Constructions of African Masculinities

|

| © Africa

Focus |

Rather than the yearned for comforts,

the advent of a democratic dispensation in Southern

Africa has thrown up many uncomfortable questions.

Many people would agree, for example, that as the

country has moved to establish a human rights culture,

crime levels seem to have risen sharply and the police,

courts and correctional services so far seem unable

to cope adequately. Some people would commend the

African National Congress government for succeeding

in providing free health services for pregnant women,

poor people and young children, but many more people

are baffled by the indecipherable strategy or perhaps

lack of will of the government to face up to strong

indications that the spread of HIV is rampant and

AIDS is plundering our communities. And while black

economic empowerment has spawned a very small nouveau

riche class, recent figures suggest that the poor

are getting poorer, and the gap between the rich and

the poor is increasing.

There is also one seemingly 'minor'

question that some critical citizens have been trying

to draw attention to because, they correctly point

out, we imperil ourselves and our entire future as

a country by paying insufficient mind to it. It may

be that this minor fact is part of all the other contradictions

South Africans are experiencing. This fact that seem

to contradict our freedom can be found in official

documents of the democratic government. For instance,

we saw it in the latest census forms. To be sure,

one will find an apology of sorts tucked away in a

footnote where writers recognize it is a contradiction,

or at least a discomforting question. But critical

researchers and scholars have also been guilty of

replaying the contradiction, even while they apologize.

The apology usually runs along the lines that this

is for statistical purposes only, or that the concerned

researchers or scholars themselves do not need to

use the category because of the history of South Africa.

The question I am referring to of course is that of

race and with that strike-through it could be argued

that am sort of apologizing.

Racial Identities

What makes the acknowledgement of race a contradiction,

it may be asked? What about race causes us to apologize?

Why do I say that it could be part of all the other

cultural, political, economic and psychological contradictions

of the new as of the old society? I think it is a

fact that race and its small-writ politics and large

one have always been and continue to be the incubus

of the South African drama. In one form or another

race is the problem of black communities and individuals

all over the racial aspect of our identities trumped

all other forms of being. Racialised identities under

pinned our everyday lives and politics. Our practices,

our institutions, our histories and our politics,

our relationships, prospects, needs for belonging,

psychic investments and fantasies, all have always

been indexed on the question of radicalized identity.

Of course (racialised) identity

is not an original South African preoccupation. South

Africa merely exacerbated it, precisely because South

Africa believed it could solve the troubles of identity

with it, even if it was to be at very great expense.

Any kind of identity is inherently a puzzle with at

least one piece always missing from the box. Identity

is fundamentally a contradiction. And as has been

said by many commentators, what we take to be identities

are always changing. So is racialised identity.

I have been talking mostly in the past tense when

talking of the race puzzle in South Africa. This may

lead to a misunderstanding. I should correct it. Much

of South Africa life is still predicted on race. That

remains a social, economic, and political affair.

We continue to believe very much in the idea of race,

and this belief, to iterate, is what lies at the centre

of the contradictions of our young democracy.

Identity Puzzle

What makes the question of identity a contradiction

is not just that one is sometimes forced to respond

with such lumpish things as Africa South African male

when, for instance, filling a visa application. Yet

this rheoretical awkwardness accentuates the ever-present

contradictions of racial and other identities. It

is important to keep this in mind especially when

one is confronted with seamless, perfect 'names' or

identities such as White South African, or African

man. In other words, when there appear to be no 'lumps'

such as 'African culture', which is another way of

saying, when the identity 'sticks' that is precisely

when we should be most suspicious.

Another form of the identity puzzle

that could be taken up is that even in the new society

the name African, for instance, does not seem to 'stick'

on white South African bodies or white citizens of

Zimbabwe. The puzzling aspect is that this is even

when the owner of the body him- or herself wants to

take the identity of African on.

Still another discussion is around

what could be called 'travel of identities'. As one

travels from one place to another, from home to elsewhere,

from workplace to dentist's room or to theatre, from

continent to continent, one has to produce an identity.

The identity one leaves home with, is not exactly

the same as the one, which is shown to a customs official,

and not the same one returns home with. The example

given about applying to enter another country can

be used again. African people and black people generally

must always travel with their race in addition to

their nationality. This then begs the questions of

when is or not racial identity more consequential

than national identity, and when is or not one or

the other of these more central to one's subjectivity.

I could speculate and argue that those called African

South Africans are generally only South Africans when

traveling, and largely Africans when at home, among

other South Africans.

Power and Contradictions

of African Masculinities

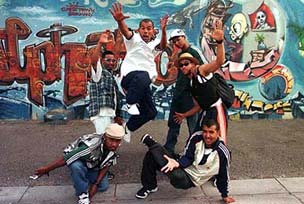

All of this points to, re-writes, re-establishes,

and plays out what goes into African masculinities,

how to turn young boys into African men, and some

of the contradictions involved. But the contradictions

I want to concern myself with here are those that

hides or shows power. I wish to posit that the emergence

of a rich class among Africans should worry us enough

to want to interrogate these African men - for most

of these rich people are men- about power. We must

interest ourselves about the lives of these African

men not just as Africans but equally if not more urgently

as men. Focusing on the sex/sexuality/gender of African

males is a deliberate and productive move of disturbing

the taken-for-granted nature of African-ness, and

of such objects as ' African Culture', 'African masculinity',

'African womanhood' and 'African sexuality'. This

move reveals the contradictions that inhere not only

in African identities, but also the inherent contradictions

of all identities.

The obvious contradiction of 'African

masculinity' is that African males 'share' one part

of the identities with African women and another part

with white/European men. If African-ness is 'shared'

between males and females then 'African masculinity'

is defined not just by African males. In the same

way, if 'the thing' that makes a man a man is something

all men know or most know something about, then white/European

males help in making African/men. Further, masculinity

is not made by males only, and there are many more

different 'types' of males than in the categories

of African and white/European, and in fact, more than

one type of masculinity; we should talk of identities

rather than identity.

The less obvious contradiction is that African masculinities,

just like other sorts of masculinities and all identities,

are sets of practices that cling together around points

of power. In speaking for or against a particular

identity, for or against the notion of African masculinities,

and in taking up or being forced to assume the identity

of an African man- that is to say instead of father,

physicist, footballer, lover, or chef- one is already

implicated in a dialogical material world that is

always structured by and around power. This means

that in discussions about African masculinities certain

voices carry more weight than others. This is in spite

of the fact that several groups and individuals 'share'

in the kind of man that ends up being built. It also

means that one raises a (real) African man, as one

raises a (real) white man- at least in South Africa-

does not simply raise a scientist or an athlete. This

is because the phrase 'just human' is an empty one,

and rather than helping us, it avoids the contradictions.

Masculinities as socialized,

embodied power

In speaking of showing the contradiction in constructions

of masculinities I am tracing a shape of a practice,

a configuration of socialized embodied power. The

shape of this practice of being man is disposed to

hide the contradictions. The more 'real' the man,

the more certain the masculine practice, the bolder

the figure, the harder the work that goes into it

and the higher the orchestration of maintaining the

original shape of the figure.

I think what Steven Mokwena's1 study on urban youth subculture showed was just this:

that the divergent, contradictory forces that went

into shaping African Masculinity were proving too

onerous to hold together. The study reported high

levels of violent practices along with survival-oriented

identities or at least imaginations. The study was

focused on the 1980s. But I think it is evident- from

the violence and crime levels in South Africa- that

we are still dealing with some of the things that

informed that youth subculture. That study explained

the violence by referring to the crisis of racist

capitalism. The study argued that the crisis created

material conditions that led to the marginalisation

of great numbers of African youngsters. These youngsters

grew up to (believe in) hustling and using violence

to get what they could not get in other ways. When

one gets to believe, one 'buys into' something, one

internalizes, one embodies. What the young African

men then may have bought into, internalized and embodied,

is exactly the violence and hustling that was first

only utilitarian.

Dominant constructions of

masculinity then and now

Now and then one observes that the dominant construction

of masculinity is still mainly of men as economic

providers; these young men must have looked to their

futures and their own sense of fulfilling their manly

future roles with a sense of ever increasing desperation.

Indeed there was no sense of looking to the future.

There was none to look forward to. These conditions

then could be said to be unhappy ones for arguing

for engagement in things like a (re) negotiation of

male identities and male power. When one is going

hungry it looks somewhat insane for some intellectual

to come around speaking about opening up and allowing

for multiple understandings of what it means to be

a man, to be African, to be a South African in the

future. As a matter of fact, the predominant sentiment

among males is that the concerns of African men cannot

be around 'niceties' of gender and masculinity. Back

then, if gender was ever broached and dominant masculinities

shown to be a problem, the reasons given for dismissing

the problem would be that African males had to deal

with more important stuff, 'bread and butter issues'

continuing the struggle. Now, if gender is broached

and dominant African masculinities shown to be a problem,

they are dismissed with laughter and arguments that

African males have to deal with more important stuff,

'bread and butter issues', deepening democracy, building

and running a country, making some money. African

men, that is to say, back then and still today, do

not have the luxury to forge new concepts of masculinity

and new ways of relating.

'Nouveau riche' and violent

cultures as two sides of the same coin

This kind of argument is oppressive and dangerous.

Pulling apart our identities, practices and institutions

and examining their constituent parts- especially

those things we are convinced we cannot live without,

our very own history and culture, our names and lives-

is always urgent. It is of such importance that it

is now insufficient to merely show the rhetoric above

as tails-side of the same coin as the rhetoric that

produces strong men as dominant, in charge, sexually-potent,

BMW-driving, platinum MasterCard-carrying managers

or owners of this and that company.

In other words, survivalist, violent,

materialistic subcultures are parts of the same cloth

as the capitalist greed that produces the African

nouveaux arrives. The racist patriarchal social structure

of apartheid, the masculine African youth subculture,

and the small band of rich Africans derive from the

vampirism of capitalism that feeds and feeds off the

idea of what it is to be a man. It may be shown then-

contrary to what may be common sense- that rather

than being free of all the structures of apartheid,

most of us are still caught up in, defined by and

supporting oppressive discourses also supported by

that racist patriarchal social structure.

I think the major point here is

that refusing to admit how in raising a boy- child

we are always implicated in power, is what imperils

the future. In making an African man, and thus reproducing

a particular, dominant identity, we must be aware

that African manhood is made within a field of power

struggles that includes such things as class, sex/sexuality/gender,

and of course race, provides at best a lopsided view

of the realities of individual African men. The worst

of it though is proceeding on the assumption of an

uncritical, uncontradictory view of a shared history

of racial oppression, while glossing over class and

sex/sexuality/gender hierarchies is part of the epistemic

and material violence that goes into constructing

African masculinities.

1 Mokwena, Steve, 'The era of the jackrollers: contextualising

the rise of the youth gangs in Soweto'. Paper presented

at Project for the Study of Violence Seminar, Wits

University, Braamfontein, Guateng, 1991.

By Kopano

Ratele, Ph.D. Dr. Ratele is a professor with the Psychology

Department and Women and Gender Studies, University

of Cape Town, South Africa. Article originally published

in News from the Nordic Institute, Nordic

Africa Institute, Uppsala, Sweden. Reprinted with

permission.

Literature on Masculinity and Race

Agenda, The New Men? Special Issue. Agenda,

Vol, 37, 1998

Berger, M., Wallis, B. and Watson, S. (eds), Constructing

Masculinities. New York: Routledge, 1998.

Brod, H. and Kauffman, M. (eds), Theorizing Masculinities.

Thousand Oaks, Ca.: Sage, 1994.

Connell, R.W. The Men and the Boys. Berkeley:

University of California Press, 2000.

Hearn, J., 'Theorizing men and men's theorizing: varieties

of discursive practices in men's theorizing of men.'

In Theory and Society, Vol. 27(6), 1998.

Journal of Southern African Studies, Special

Issues on Masculinities in Southern Africa, Journal

of Southern African Studies, vol 24(4), 1998.

McCall Nathan, Makes Me Wanna Holler: A Young

Black Man in America. New York: Vintage Books,

1995.

Moodie, T.D with Ndatshe, V., Going for Gold:

Men, Mines and Migration. Johannesburg. Wits

University Press, 1994.

Morrell, Robert (ed), Changing Men in Southern

Africa. London: Zed Books, 2001.

|